Prof. Rob Watts is a professor in the School of Global, Urban and Social Studies at RMIT University, and was a guest speaker at FAIN’s 2025 Annual General Meeting. This is the notes from the speech he gave at our AGM.

Australians have long liked to describe themselves as living in the land of the ‘fair go’, where class doesn’t matter and we are all equals; after all don’t most of us like to sit in the front seat of the taxi. Andrew Leigh an economist turned Labor politician, argues that:

Egalitarianism goes deep in the Australian character. Most of us do not like tipping. There are no private areas on our beaches. Audiences do not stand when the prime minister enters the room.

Surveys like Australian National University and Social Research Centre survey (2015) suggest that around 92 per cent of Australians describe themselves as belonging to either the working or middle-class, with only 2 per cent admitting to belonging to the upper class. The remaining 6 per cent ‘didn’t know.’

Yet in 2025 it is now perfectly clear that too many Australians are bearing the cost of serious inequality, which has been getting steadily worse over the past few decades. As the highly regarded annual Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) report for 2024 showed, inequality in Australia is at its highest since the HILDA Survey started in 2001.

Increasing inequality in the distribution of income and wealth has adverse economic, social, cultural, psychological and political consequences. ANU economist Andrew Leigh, now the MHR for Canberra treats the idea that inequality has been increasing as a truism. Leigh argues that:

… that inequality is a growing problem that should be addressed. A high-inequality society is a highly unstable society. When assets in a society are distributed in a way that most people believe is unfair, it creates a form of systemic risk. … When we look at the rise of populist politics around the world, it’s clear that inequality helps foster the sense that mainstream politics isn’t delivering. … A more equal nation will have higher levels of wellbeing, more mobility, and more stability.

Let us agree that inequality matters and I think we can and that we should do something about it.

- What is actually happening? How do we know it?

- How might we best explain what is actually happening

- What should we do to do better?

What is actually happening?

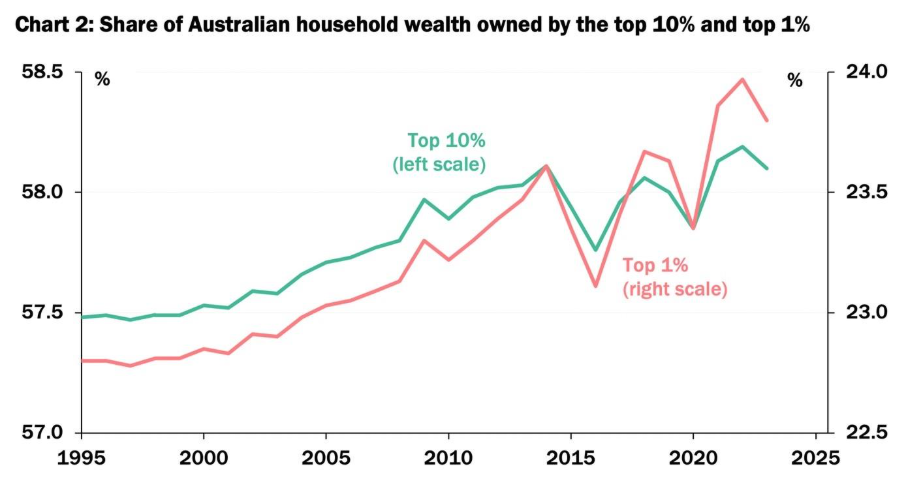

We are now seeing unprecedented and unjustifiable levels of income and wealth inequality. The problem not soaring poverty but increasingly rampant levels of concentrated and toxic wealth: Australian billionaires’ wealth has soared by $120 billion since 2020 while ordinary people’s real wages has barely increased. Throughout most of the period since 2015, real wages growth has been negative with the exception of some partial catch-up in 2018 and 2019 and again in the year to March 2025 which saw, Australia’s nominal wage growth grow by 3.4 per cent representing a 1% increase in real wages. We are seeing a really unhealthy increase in wealth inequality as the Chart below indicates:

This unhealthy concentration of wealth is closely connected to many other problems including

- the so-called ‘inflation crisis’

- soaring cost of living

- increasing unaffordability of housing

- skyrocketing private debt levels

- 60 years of declining labour productivity

- the return of precarious employment such as we once had into the 1930s

- the negative impact of generative and agentic Artificial Intelligence on many low skilled service jobs and some middle-level professional jobs

There are many important harmful consequences of this crisis of inequality. The one I want to emphasise today is that we have created a serious problem of intergenerational equity or fairness.

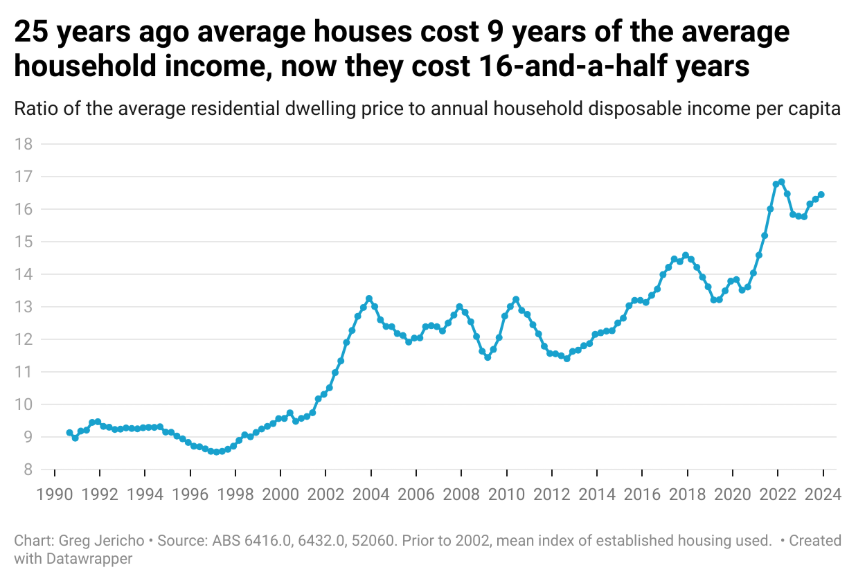

This is. especially evident in the housing crisis which affects many young people under 35. The problem is the increasing gap between wages incomes and housing costs. (See Graph below)

Put simply and unlike all previous generations going back to the start of the nineteenth century, young people born since the late 1990s are not doing as well as their parent’s or grandparent’s generations. As I showed in an earlier book (The Precarious Generation) (2017), this state of affairs is hardly unique to Australia: many countries in the wealthy OECD societies. now confront the same scenario. You’ll see soon enough why I emphasise this.

Whether this has to do with reduced income, increased debt, precarious or uncertain career opportunities, crappy schools and universities, declining literacies, difficulties accessing decent housing, mental health issues, or the looming catastrophe of climate change, young people face a world of trouble.

This state of affairs has undone the tacit social contract between the generations which presupposed that each new generation would be able to live better and lead more flourishing lives than their parents had done.

How to Explain What is Actually Happening

If we are to explain this situation there are two basic connected explanations. Much of this crisis of inequality is the result of (i) the confluence or conjunction of half a century of deliberate policy-making introduced by all sorts of governments and the fact (ii) that capitalism is transforming itself in radical new ways which threatens to end the centuries old relationship between capital and labour and engineer whole new ways of seeking profit.

Firstly, and put simply we are now seeing the result of five decades of neoliberal policies adopted by many governments around the world. It doesn’t matter whether they called themselves far right, conservative, Democrat or republican progressive or labour or even the CCP, they all adopted key policies.

The first proximate explanation why all of this is happening is because neoliberalism has not gone away. While the twin crises of the GFC in 2008 and COVID 19 (2020-2023) saw policy responses that seemed to signify the end of neoliberalism. The policy settings of neoliberal governments whether of the center-right or the center-left have been driving the radical transformation of capitalism since the 1980s. Weakening unions, tax breaks for the wealthy and privatisation have a symbiotic relation to the rise of dramatic levels of public and especially private debt, the rise of a vast and unregulated derivatives market, the take off of fintech including surveillance capitalism, and the AI revolution which is threatening to obliterate the old labour-capital relation.

This package of neoliberal policies was precisely designed to skew the share of income going to labour in favour of capital ensuring that the share of wealth and income going to the top 10% soared while the middle was hollowed out…

- The Hawke-Keating government deregulated the dollar in late 1983.

- The Hawke-Keating government deregulated the banking financial sector beginning in 1983 unleashing decades private debt, and criminal and corrupt practices in the banks insurance companies, and casinos.

- The Hawke-Keating government set about fatally weakening the unions while enhancing management prerogatives all under the umbrella of a succession of Accords.

- The Hawke-Keating government introduced waves of tax reform including tax avoidance schemes worth hundreds of billions (Negative gearing), a tax framework which last year saw companies like QANTAS, Netflix and Mastercard pay not a cent in tax The Howard government introduced non progressive sales taxes like the GST which savaged low income families.

- The Hawke-Keating government began he process of selling off valuable public sector entities including energy, banks, utilities, and telcos for a song.

- The Hawke-Keating government slashed university funding, abolished free university education introduced debt based loans schemes to ensure university student paid tuition fees. Any any revenue shortfall would come from international students (In 2024 this was our fourth biggest export industry worth $51 billion.

- The Hawke-Keating government began the process of insisting that public services either be handed over to NGOs or else be turned into for profit enterprises including child care, aged care, public transport, and health and education.

- Later governments tore down any tariff barriers in favour of free trade treaties which killed off any local manufacturing and industrial capacity while encouraging the rapid development of new forms of rentier capital.

Secondly we are seeing a radical transformation in the way capitalism now works, a process enabled by the hegemonic status of neoliberal politics Put simply the centuries old relationship between capital and labour is coming to an end as again a century of applying new technologies to increase productivity is now morphing into a new digital labour force comprising robots algorithms, chat bots and generative and agentic AI.

Economically global capital has been transforming itself moving away from industrial production in the big developed economies and evolving into Fintech involving the mating of unregulated financial capital and digital net based platforms relying on surveillance capital and more recently predictive AI algorithms, and now generative and agentic AI.

This is happening faster than anyone had imagined. There is huge hype deliberately designed by Google, Microsoft etc to sucker in new investment but there will be serious and real consequences.

What Should We Do to do Better?

The short answer -as always- when faced with these kinds of circumstances is take Winston Churchill’s advice: never let a crisis go to waste. The good news is that if what we are seeing now is a product of decades of toxic neoliberal politics and policy making , we now need to do some serious political work. So let’s get political.

My big point? In this instance one clue to what need to be done comes from an earlier observation about the cost of rising inequality borne in large measure by young people. There is now a crisis in intergenerational fairness and injustice especially borne by today’s young Australians but also and unsurprisingly by many older Australians. So what is to be done?

1. We need to build intergenerational solidarities and intergenerational movements that cross generations and make real the point that we want intergenerational justice and we want to restore intergenerational justice and we mean to do it -now.

2. We also need to learn from successful cross generational campaigns and movements and we need to then apply what has been learned. The Knitting Nannas eg., tell us about the role played by humour self deprecation irony and wit and laughter what has worked:

- Tamp down the critique and ramp up the positive vision of a fairer decent Australia

- Increase the fun and laughter in our political activity

- Do the hard work holding governments and corporates to account -visit offices, set up Knitting Nanna circles outside offices, hold MPs accountable, follow up with letters asking questions, demanding to see documents and records

- Reach out actively to youth-led movements, other activist groups and networks and offer solidarity and support

- spend time listening consulting with ordinary Australians whether young, middle-aged or older

- spend lots of time developing new laws and new policies that change the rules of the game.

We need to oppose those things that matter and do so on a cross-generational basis. We should certainly oppose things such as:

- Approving gas and coal mining licences,

- Human rights abuses of young people indigenous people,

- unfair treatment of social security beneficiaries,

- pro-war industries and agreements.

But if protests are good, so too e.g., is strategic litigation bringing together young and old. (Like the Sharma case in 2021). Explore the option of legal court action (from FOIs to VCAT to Supreme or federal Court action) to challenge wrong or unfair government or corporate policies relying on human rights and duty of care principles. Work with pro bono lawyers.

We need to hold our current democratic representative to account. We need to put the pressure on todays elected representatives. Hold them to account; ask difficult questions; visit them, write letters and let them know we are aren’t happy.

Develop and do the research set up Citizens Assemblies to consult with and take advice from ordinary citizens and make the central participatory principle clear in any democracy worth its name: nothing about us -without us! Equally importantly we need to do serious policy reform work.

Work to develop a systematic legislative reform agenda which might include:

- Major overhaul of the tax law

- Reform the Environment Protection Act inserting a duty of care principle

- Introduction of an Australian bill of rights based on UNC ICPR, UNC SECR, and UN CRC with serious remedies and enforceability

- Reform the e-safety Act and regulate the major social media platforms to prevent them from ruthlessly harvesting everyone’s personal data

- Regulate the OTC derivatives and crypto coin markets

- Design and introduce systematic democratic accountability legislative framework for all three levels of government increasing the accountability mechanisms, beginning with strong FOI provisions.

Now it’s time to get political.

– Prof. Rob Watts

2 thoughts on “Some Notes on Inequality in Australia – and What to Do About It, by Rob Watts”